Written by Michael Head

Writing nine months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, magazine publisher Henry Luce penned ‘The American Century’ in Life. Within this article lay a clear articulation of the politically liberal and fiscally conservative values which would permeate post-war Americanism, with an emphasis on ‘a love of freedom, a feeling for the equality of opportunity and a tradition of self-reliance and independence.’1 As Stephen Whitfield argues, ‘the search to… affirm this way of life, the need to express and celebrate this meaning of “Americanism,” was the flip side of stigmatising Communism,’ an ideology viewed as explicitly un-American.2 This essay will argue that un-Americanism served to constrict the grounds for legitimate debate within the political-military institutions of the Cold War national security state, whilst simultaneously strengthening conformity around the social institutions of everyday life. In other words, this essay will highlight how anti-Communism espoused within the public sphere served to reify the suburban, middle-class nuclear family and seemingly popularise its attendant socially conservative outlook with regards to gender, sexuality, consumerism and religion.3

Un-Americanism in the public sphere

The immediate post-war years demonstrate clearly the pernicious impacts of the concept of un-Americanism upon the politics of the Cold War national security state, an apparatus which, as will be demonstrated, was capable of manipulating attitudes towards gender and sexuality at the level of the neighbourhood.4 Here, Arthur Schlesinger Junior’s 1948 work The Vital Centre, written amidst the drama of the Alger Hiss espionage case, is worthy of discussion.5

The Vital Centre, in Schlesinger’s view, was the site where patriotic liberals and conservatives could meet and achieve consensus, thus protecting what Wendy Wall labels ‘America’s package of freedoms’ – free enterprise, abundance, security and worship.6 Schlesinger, guided by fervent anti-Communism, viewed the far Right as ‘an exhausted, spent masculine potency’ and ‘the progressive Left as lacking sufficient masculinity’ in the protection of such freedoms.7 Calling for the revival of the “tough minded” radical Democrat, Schlesinger placed great emphasis upon a ‘mature appetite for decision making and responsibility.’8 Vital Centre liberalism would be increasingly vindicated in the late 1940s and early 1950s: Mao’s victory in 1949 and the grinding stalemate of the Korean War appeared to confirm the absence of ‘masculine potency’ amongst the nation’s leaders.9

Amongst the package of freedoms Vital Centre liberalism was charged with protecting, the free enterprise and equal opportunity central to post-war national identity was buoyed by the state’s effective readjustment to a peacetime economy. By 1950, the US was enjoying the world’s highest living standards, producing and consuming over a third of the goods and services of the planet and witnessing the rapid growth of its middle class.10 Growing affluence supported the broader Red Scare, contributing to Henry Wallace’s limited success as the Progressive Party’s candidate at the 1948 Presidential Election.11

The coalition of Liberals, Trade Unionists and Communists which shaped Popular Front radicalism in the New Deal era was upended by the emergence of a virulent, patriotic anti-Communism which envisaged limited political space for radical, leftist politics and yet held a broad and consistent appeal, reflecting upon the longer history of consensus politics surrounding the phenomenon of the “American Way.”12 This ultimately ensured the limited success of Truman’s Fair Deal, given that further expansion of the welfare state – through, for example, the establishment of national medical insurance and federal aid to education – would contradict the claim that free enterprise and personal independence were central to the “American Way of Life” so antithetical to Communism.13

These civic nationalist principles underpinning the politics of un-Americanism also ensured that the ‘“radical other” began to lose ethnic or racial connotations.14 This helped materialise the 1952 McCarran-Walter Act, which removed the blanket ban on Asian immigration and enabled first-generation Asian immigrants to naturalise as US citizens.15 The 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision was also influenced by this weakening of racial nationalism.16 By the mid-1950s, this encouraged the core of the Civil Rights Movement to adopt peaceful, legalistic forms of protest, emphasising how democratic rights and freedoms – central to America’s international legitimacy in the ideological contest against Communism – were an entitlement to all citizens, regardless of race.17

Un-Americanism in the private sphere

This fundamental change in political culture fused with what Gary Gerstle coins the ‘Rooseveltian mould of nation building.’18 This entailed disciplinary campaigns within the political-military institutions of the state which served to ‘strengthen national ideals whilst silencing those whose politics and culture [and behaviour] threatened national cohesion and purpose.’19 This was the rationale underpinning Truman’s controversial Federal Employee Loyalty Programme, the purging of over 600 proven and suspected Communists from America’s universities and the resignation of 91 State Department officials during the ‘Lavender Scare,’ which linked homosexuality to the subversive and clandestine activities of Communism, in step with the masculine verities of Vital Centre Liberalism and Roosevelt’s emphasis on strict discipline and visible conformity.20

J. Edgar Hoover would typify the discipline required to effectively police un-Americanism in the 1950s. As the number of FBI agents and informants grew in an increasingly regulated political culture, he stated:

“When a young man files an application with the FBI, we do not ask if he was the smartest boy in his class… We want to know if he respects his parents, reveres God, honours his flag and loves his country.21

Hoover’s critique of a young man’s faith and connection to family demonstrates how un-Americanism facilitated the powerful influence public and private life had upon each other throughout the early post-war period. As Elaine Tyler May argues, the families formed by middle class Americans during the 1950s were ‘shaped by the historical and political circumstances that framed their lives.’22 Charges of Communist un-Americanism contributed to the ‘neo-Victorian revival of family life’ which would be seen as a moral bulwark against subversion throughout the 1950s.23

By 1960, the conceptual link between un-Americanism and Communism had united the policing of Communism in the public sphere with the social conformity of nuclear families throughout the suburbs, a ‘civil defence strategy’ which was believed to protect national security.24 As James Patterson concludes, ‘the quests for personal security and domestic security became inextricably interrelated’ by midcentury.25

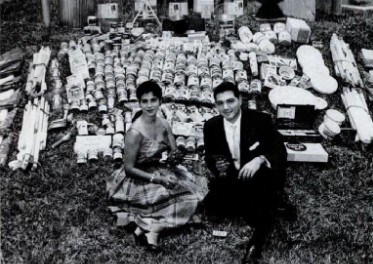

Just as Henry Luce provided his politicised vision of the American Century in 1941, in 1959 Life published a photographic essay illustrating the denouement of the concept within the American suburb through the so-called “Atomic Honeymooners” Melvin and Maria Mininson:25

Retrospectively, the image of newlyweds takes on symbolic significance in the context of post-war un-Americanism. Heterosexual marriage was viewed to temper the ‘official and popular anxiety’ about the dangerous nonconformity of homosexuality increasingly linked to the clandestine activities of Communism.26

The Mininsons marriage can therefore be seen as a microcosm produced by the Vital Centre liberalism which pervaded early post-war politics, something which would lead Congress to produce the 1950 report Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts in Government.27 This argued that liberals, communists and homosexuals were united in their common moral weakness, emotional instability and susceptibility to enemy blackmail.28 Un-Americanism therefore served to reify heterosexual marriage as a defence against Communist infiltration and moral subversion amongst the growing middle class, serving as a bastion of national defence and linking closely the public and private spheres of American politics and society.

This was but one part of the growth of “symbolic politics” catalysed by the concept of un-Americanism.29 The canned goods surrounding the Mininsons point to the growth of consumerism throughout the 1950s, ‘the means for achieving a classless ideal of individuality, leisure and upward mobility.’30 The geopolitical exigencies of the Cold War converged with the growth of American affluence and rendered the suburban home – and its associated comforts – a key defence against Communism. This was clear in the famous 1959 “Kitchen Debate” during the American National Exhibition in Moscow.31 Everyday modern kitchen appliances were used by Nixon to demonstrate the ability of American capitalism to build a bridge between the ‘strong, prosperous and happy family and a strong, prosperous United States,’ devoid of the pernicious and subversive class conflict deemed central to the Soviet Union’s ideology and the root of its people’s destitution.32

However, it should be noted that the ‘classless ideal’ supported by the post-war consumer boom was still conditioned by the gendered lens placed by fervent anti-Communists upon 1950s Cold War politics, the same emphasis on masculine dominance which villainised the New Dealers and Ivy Leaguers of the late 1940s and their perceived effeminate appeasement of expansionist Communism in Europe and Asia.33

This can be inferred through the 1958 phenomenon of the Barbie doll.34 The idealised femininity of the Barbie doll can be emphasised in contrast to the premium placed upon virulent masculinity in the public sphere. In this sense, Un-Americanism supported the reassertion of distinct gender roles within the walls of the suburban home as means to prevent wider Communist subversion.

This upheld the dominant binary of male breadwinner and female homemaker, with particular emphasis upon the maintenance of a wife’s appearance and subservience and a mother’s central role in raising the patriots Hoover would seek to recruit well into the 1970s.35 As Joanne Meyerowitz concludes, whilst there was greater impetus for allowing female wage work and political activism – as means to highlight the masses living under authoritarian rule behind the Iron Curtain – ‘marriage and motherhood stood strategically at the literal and emotional centre.’36

Uniting the revival of family and domesticity with the state’s liberal emphasis on civic freedoms and critical focus on sexual conformity was the renewed moral value found within the Christian faith, something underscored by the official atheism of the Soviet Union.37 Church membership rose from 64.5 million in 1940 to 114.5 million of the entire population in 1960, a 13% increase.38 “One Nation Under God,” America sought to differentiate itself from godless Communism; Reverend Billy Graham even claimed that Communism was the work of Satan.39 The aforementioned association of Communism with underground nonconformity and moral subversion emphasised the value of holding religious faith as inner affirmation of being an American patriot.40 Christianity therefore gifted a sense of wholeness and moral urgency to the socially conservative worldview imbued within the nuclear families of the fifties.

Conclusion

Despite the claims made by American intellectuals like Daniel Boorstin, post-war un-Americanism was far from an ‘anti-metaphysical’ concept, devoid of extremist tendencies. 41 Political debate within the national security state became increasingly exclusionary along the lines of free enterprise and virile, masculine liberalism. Society – particularly middle-class suburbia – became increasingly uniform, orbiting around heterosexual marriage, capitalist consumerism, traditional gender roles and the pervasive influence of Christianity.

The anti-communist unity of mainstream politics and society during this period enabled the effective policing of un-Americanism in the public and private spheres. This implies Cold War Americanism was a far more coercive concept than the popular and intellectual culture of the time suggests. It was also a concept which established an “aura of unreality,” a conformity seemingly so perfect, so as not to be real at all.42 The rise of the New Left and the crushing loss of masculine credibility in the wake of Vietnam would, in the end, confirm as much.

Footnotes

- Henry R. Luce, “The American Century,” Life, 17 February 1941, pp.61-65.

- Stephen J. Whitfield, The Culture of the Cold War, (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

3 Elaine Tyler May, “Cold War – Warm Hearth: Politics and Family in Post-war America,” in The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order, 1930-1980, ed. Steven Fraser and Gary Gerstle (Princeton University Press, 1990).

4 Geoffrey S. Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation: Sex, Gender and Disease in the Cold-War United States,” The International History Review, Vol.14, No.2 (May 1992), pp.307-337.5 James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974, (Oxford University Press, 1996)

6 Wendy W. Wall, Inventing the American Way: The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement, (Oxford University Press, 2008).

7 K. A. Cuordileone, ‘“Politics in an Age of Anxiety”: Cold War Political Culture and the Crisis of American Masculinity, 1949-1960,” Journal of American History, No.87 (2000), pp.515-545.

8 Ibid, p.520.

9 Smith, “Personal Isolation,” p.315.

10 Whitfield, Culture, pp.69-70.

11 Patterson, Grand Expectations, p.186.

- Ibid, p.183; Wall, Inventing the American Way.

- Ibid, p.158; p.178.

- Gary Gerstle, American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, (Princeton University Press, 2001).

- Ibid, p.257.

- Ibid, p.250.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, pp.239-41.

- Ibid.

20 Patterson, Grand Expectations, p.187; p.198.

21 Ibid, p.65.

22 May, “Warm Hearth,” p.156.

23 William L. O’Neill, American Society Since 1945, (Franklin Watts Incorporated, 1969).

24 May, “Warm Hearth,” p.161.

25 Patterson, Grand Expectations, p.181.

- “Their Sheltered Honeymoon,” Life, August 10, 1959, pp.51-52.

- Smith, “Personal Isolation,” p.315.

- Cuordileone, “Anxiety,” p.533.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p.516.

- May, “Warm Hearth,” p.158.

- Ibid.

- Smith, “Personal Isolation,” p.330.

- Cuordelione, “Anxiety,” p.533.

- Whitfield, Culture, p.71.

- Joanne Meyerowitz, “Beyond the Feminine Mystique: A Reassessment of Post-war Mass Culture, 1946- 1958,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Mar., 1993), pp. 1455-1482.

- Ibid, p.1470.

- Whitfield, Culture, pp.80-83.

- May, “Warm Hearth,” p.163.

- Whitfield, Culture, p.81.

- Ibid.

- Ibid, p.54.

42. O’Neill, American Society, p.8.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

- Henry R. Luce, “The American Century,” Life, 17 February 1941.

- “Their Sheltered Honeymoon,” Life, August 10, 1959.

Secondary Sources

- Elaine Tyler May, “Cold War – Warm Hearth: Politics and Family in Post-war America,” in The Rise and Fallof the New Deal Order, 1930-1980, ed. Steven Fraser and Gary Gerstle (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990).

- Gary Gerstle, American Crucible: Race and Nation in the Twentieth Century, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2001).

- Geoffrey S. Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation: Sex, Gender and Disease in the Cold-War United States,” The International History Review, Vol.14, No.2 (May 1992), pp.307-337.

- James T. Patterson, Grand Expectations: The United States, 1945-1974, (Oxford University Press, 1996).

- Joanne Meyerowitz, “Beyond the Feminine Mystique: A Reassessment of Post-war Mass Culture, 1946-1958,” The Journal of American History, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Mar., 1993), pp. 1455-1482.

- K. A. Cuordileone, ‘“Politics in an Age of Anxiety”: Cold War Political Culture and the Crisis of American Masculinity, 1949-1960,” Journal of American History, No.87 (2000), pp.515-545.

- Richard M. Fried, Nightmare in Red: The McCarthy Era in Perspective, (Oxford University Press, 1991).

- Stephen J. Whitfield, The Culture of the Cold War, (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

- Wendy W. Wall, Inventing the American Way: The Politics of Consensus from the New Deal to the Civil Rights Movement, (Oxford University Press, 2008).

- William L. O’Neill, American Society Since 1945, (Chicago: Franklin Watts Incorporated, 1969).